In the Afterword of the Vintage Classics American Gothic Collection edition of Fight Club, Palahniuk recounts a run in with a fan of the film adaptation, someone who didn’t even know Fight Club had started life as a book. He uses this to explore the building of the story, the mythology that surrounds it, the tales of mischief and violence he has been gleefully welcomed into, and the writing of the short story which would go onto become this cult classic.

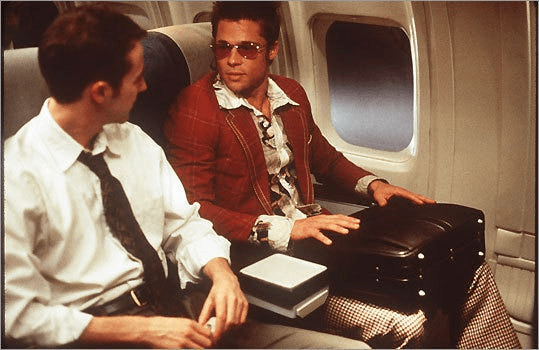

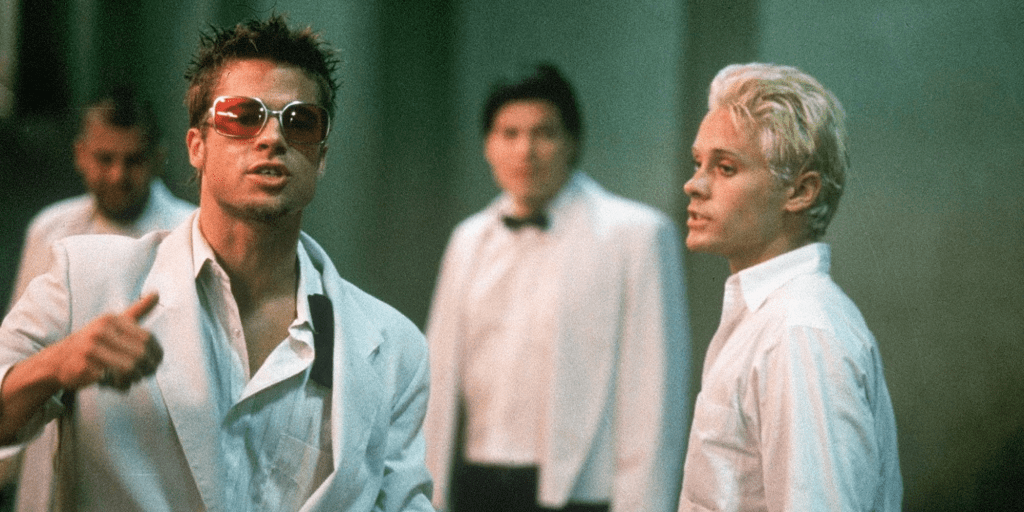

We’ve all seen it, or most of us have anyway. Brad Pitt, all shaved head and sweat, Ed Norton, hollow and haunting, and Helen Bonham-Carter, wild haired and wild eyed. They command presence, the screen washed in blue-tint long before Twilight’s eerie vampires, but this film is more than a thespian tour de force, it is a faithful adaptation. For the most part. So faithful, in fact, that the novel becomes almost familiar, the story line haunting, your knowledge of what is to come only intensifying the build towards the twist. The narrator isn’t just unreliable, there is a sense of dramatic irony only surpassable by Arthur Burling’s assertion that the Titanic will not sink, and the World War will not happen. And just like An Inspector Calls we are returned suddenly to the beginning, or rather, to the end, time collapsing perfectly, so we can see how all that has passed is present.

I have a lot to say about this book, but in many ways it is irony I want to stay with. A different kind of irony, an irony tied inextricably to the film, to masculinity, to the importance of English Lit and media literacy, and, ultimately, to queerness.

Fight Club is, and will likely remain, one of those films. Like The Matrix, Pulp Fiction, American Psycho, Taxi Driver, or even Star Wars which becomes emblematic of male fandom. These are the movies that women even mentioning send scores of men into comment-section frenzy; the films most likely to be mansplained to you on Twitter (I will not call it X, bite me); the films which are trotted out again and again by alt-right mouthpieces who have never bothered to critically engage with the content. It is in that failure to engage, to participate in such girlish, wimpy, academic pursuits as analysis, that these individuals fall down. Fight Club is one of the gayest books I have ever read, and I did an MA module on Queer Lit. It isn’t just homoerotic in the literal definition sense, that is, concerned with things which men find interesting and attractive, but homoerotic in the internet-casual-use sense, that is, concerned with sexual and romantic attraction between men.

Just like Jekyll and Hyde, lycanthropy, and vegetarianism (shout out to my good friend Mass for reminding me of that last example recently) the dual personalities in Fight Club can be read as a metaphor for queerness. We have the unnamed narrator, presumably our primary personality, who is living a half life. He is repressed, denying himself everything, even sleep. He finds solace in the feminine bosom of a large, masculine man, whose pursuit of homoerotic beauty (huge muscles) have had an ironic counter-effect. Bob is ball-less and boob-full. Bob is the only thing that helps our narrator sleep. This alone is ripe for queer reading, the interplay of gender and secondary sex characteristics, the sexless reality of Bob, the fact that the narrator ingratiates himself only by faking his own castration, and the fact that all of this is interrupted by the arrival of Marla. Marla is, in many ways, the trigger, the thing that arms the time-bomb that is our narrator.

He first meets Tyler Durden on a beach, sitting within the palm of a hand he has constructed from drift wood. Our narrator likens this to sitting in the palm of God, but in truth he is observing the moment when his creation, Tyler, sits within the hand of ‘God’, even though he, the narrator, is Tyler’s God. We know, having read the book or seen the film, what the twist is, and so this becomes a multi-layered exchange. The narrator has built the hand of God, and stepped back to view his creation sitting in its shade. He is the creator of all he surveys. He also, it must be said, is about to walk across a beach and leave only one set of footprints. The narrator thinks Tyler is beautiful, and well he should, Gods should find beauty in what they construct. But the narrator is also taken in by Tyler. We might ask ourselves if this is a God [narrator] constructing man [Tyler], or a man [narrator] constructing God [Tyler]?

Regardless of where you stand on that argument, Tyler comes to exist after Marla upsets the balance. He personifies a part of the narrator which can no longer exist harmoniously within the narrator’s whole. In a lot of dual-identity / shifter / hidden aspect narratives the dark side, (the Hyde, or wolf, or vegetarian truth of the character) is the ‘queer’ element; those readings rely on the inherent ‘wrongness’ of queer identity, as cemented into social consciousness by decades of oppression and fear-mongering from (typically) conservative and/ or religious sectors. Conversely, in Fight Club, the other element, the Tyler Durden faction of the narrator’s self, is heterosexual. He begins a sexual relationship with Marla which the narrator neither understands, nor desires. The narrator routinely tells us of the beauty of other men, including Tyler, and a young man who he finds so beautiful he must touch him – fight him, in fact. When he needs to leave his job, the Tyler element of his personality uses only blackmail, the narrator portion constructs a fake altercation, closing himself in a room with another man, and faking a physical interaction (albeit a violent one). The narrator is also the primary personality we see involved in fights, repeatedly establishing an excuse to maintain close physical contact with other men. He typically looses these fights which, to again hark back to the same old school English Lit great-big-long-list-of-pre-established-literary-norms which tells us the bad personality is the gay personality, establishes him as the more submissive partner in interactions which effectively mimic sexual intercourse – the narrator is the receiver.

When you consider that reading alongside the plot trajectory, Fight Club reveals itself to be something quite different to a violence fuelled, toxically masculine, call to arms for the disenfranchised… when you read it with all of its queerness, Fight Club is a coming out narrative. Here we have the narrator, whose queer identity he couches in violence, and enshrouds in catalogue perfect average-mid-working-class-white-bachelor-ness. He has IKEA furniture, and he works a solid, mid-level job. He is also, as we have explored, miserable, and seeks solace amongst others who have things eating away at them or who have been desexed – in fact, almost all of the support groups we are told about involve a poisonous, inside-eating, parasitic, tumorous condition, and / or becoming impotent. This could be read as kind of internalised homophobia. The narrator denies himself joy, he is consumed by his misery, he seeks the company of other people dealing with internal, painful conditions, and / or those whose sex-lives are forever changed by their conditions. He finds joy, and sleep (release) only when he begins to interact physically with other men, only when he achieves his desires, becoming the receiver in symbolic same-sex intercourse.

At the same time, the part of him that is ‘straight’, the masculine, hard part of him that had been denying his true nature, is extricated and begins not just a sexual relationship with a woman, but a campaign of dominance and subjugation: branding and controlling other men, reacting in the most extreme inverse ways to the behaviour of the narrator. Tyler is a giver. We also see the relative perversity in this aspect of the narrator in the actions of Tyler Durden, splicing pornography in children’s movies; tainting food stuff with bodily fluids (notably the only on page example of this also involves his penis – hard to imagine that isn’t relevant); stealing human fat. Ironically, however, extricating this aspect is what leads the narrator to physically involve himself in a heterosexual relationship, and which also allows the narrator to explore his homoerotic desires. By the end of the story, as the narrator comes to understand who and what Tyler is, he seems also to understand himself more. He realises he does love Marla, just not romantically or sexually, she has become a friend to him.

He also realises what a corrupting influence Tyler is, of particular note is when he sees the beautiful young man from before, who is no longer beautiful, something he has lost due to his commitment to the cause. Finally, the narrator seemingly comes to terms with his own death. Killing Tyler, the part of him that is controlling, which is ashamed by the narrator, can only be achieved by killing himself. It is not clear from the novel if they both perish, of if the narrator kills off the ‘him’ part of his mind – either way it becomes apparent that they cannot coexist anymore. The narrator would rather die than continue to be corrupted and / or subjugated by the hetero-extremist, toxically masculine elements of his personality.

It is this rejection of Tyler, and willingness to die, that holds this back from being read as a bisexual narrative – in my opinion. Although we have the interplay of heterosexuality and homosexuality (represented by each personality), which are further enforced by the oppositional roles the identities within in symbolic intercourse (giver and receiver), their is not a sense of ‘bothness.’ Tyler is not attracted to men, and the narrator is not attracted to women. Tyler does not want to be fucked, and the narrator is not especially interested in fucking. There is on exception to this, the aforementioned beautiful man, who is described in a way that is arguably feminine, and whom the narrator beats into submission – taking on the role of giver. Even considering this, however, one might argue that it does not conform to a bisexual narrative, although the narrator takes on a more masculine role in that one interaction, Tyler eventually wins the beautiful man as an acolyte, without seemingly taking on the feminised role of receiver at any time. There is no reciprocity. One could posit, and I do think this is arguable / evidence-able, that this is a bi-phobic narrative, a kind of rejection of bothness through the stark separation of hetero and homosexual identities. To be clear, I am suggesting a theoretical biphobia, I don’t think it would be fair to suggest such a reading through an authorial intention lens.

So here we are. Fight Club is, as I hope to have at least strongly argued if not proved, a deeply queer novel. So why is it that Fight Club has also become something of a red-pill, incel-adjacent, toxically masculine icon? In no small part we should blame anti-intellectualism, and such memes as the (ever unamusing) blue curtains schtick. In a world where critical engagement is neither cool nor especially popular, it is easier to engage with only the top level of something. To look at a film, especially, like Fight Club and say, ‘sex, violence, nihilism, and depravity? Cool!’ rather than to look at a film like Fight Club and see it as something that at once attempts philosophy and romance, action, violence, and deep wrought emotion.

If you haven’t read it, you should, and if you have, let me know your thoughts.

Leave a comment